:quality(80)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/dreamstime_m_73490992.jpg)

In 2020, Covid-19 narrowed the prosperity gap between rich and poor countries as the former were at first the most affected. In addition, the crisis may also have accelerated long-term structural trends that will not be favorable to many emerging economies.

Covid-19 will increase income inequality between richer and poorer countries since the latter have less policy room to mitigate the impact of the crisis and slower access to vaccines. In addition, the crisis may also have accelerated long-term structural trends that will not be favorable to many emerging economies. In the post-Covid-19 world, the comparative advantages of relatively cheap labor – on which the rise of emerging markets and the global middle-class was primarily based – would count for less. In this context, the path to high-income status could become longer and more difficult for these countries.

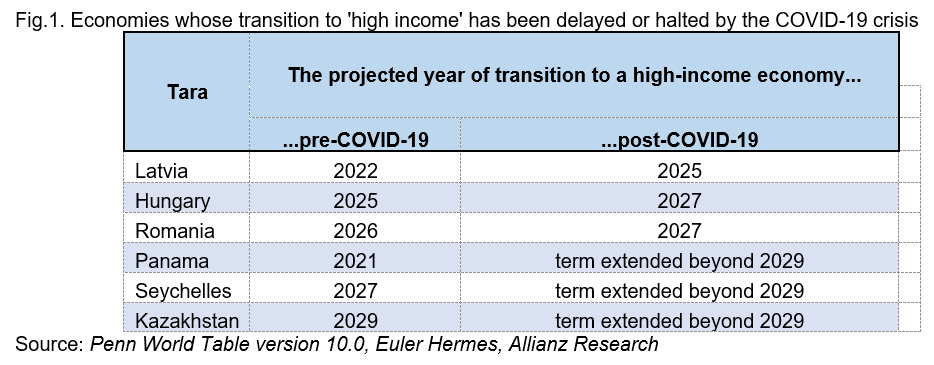

To analyze the potential long-term effects on per capita income, Euler Hermes analysts have paid close attention to the risk of a “middle-income trap”. Based on pre-crisis and post-crisis long-term economic growth forecasts, the research finds that by 2029, Hungary, Romania and Latvia are likely to see their transition delayed by a few years, though their EU membership will prevent a descent into the middle-income trap. Indeed, Romania has seen a steady increase in per capita income until 2019. Initially, it was predicted that Romania would make the transition to the group of high-middle-income countries by 2026 at the latest, but the Covid-19 crisis is delayed. this time the forecast with another year.

However, Kazakhstan, Panama and Seychelles will not move to high-income status during the forecast horizon. Somewhat surprisingly, Turkey and Russia could achieve high-income status in the medium run sooner than previously expected, likely due to crisis-related fiscal stimuli. Kazakhstan could have a delayed transition as pre-crisis forecasts suggested that it would reach high-income country status in 2029. For Seychelles and Panama, their long-term development could be hampered by the impact of Covid-19 on tourism and by the historical agreement on a minimum rate of income tax. These three countries are thus most at risk of being pushed into the middle income trap by the Covid-19 crisis.

Euler Hermes’ long-term recovery trend analysis identified 10 countries (Argentina, Bulgaria, Colombia, Croatia, Greece, Laos, Nigeria, Slovakia, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay) that are or will be trapped in average incomes. Many of these were, are and will be included in the group of middle-income countries in the period 1950-2029. Greece, Trinidad and Tobago were among the economies that switched from the high-income group to the middle-income group before the Covid-19 crisis. There are many reasons why some countries remain trapped in this trap, but the role of insurance markets is essential. The two South American countries, Argentina and Colombia, for example, have a significantly lower penetration in insurance than the richest country in the region, Chile. On average, over the last 25 years, the difference has been between 1.3 pp (Argentina) and 1.7 pp (Colombia). The situation is similar in the three Eastern European countries Bulgaria, Croatia and Slovakia. Compared to the Czech Republic and Poland (unweighted average), insurance penetration has been about half a percentage point lower in the past.

In this context, the insurance market has a key role to play. Insurance helps countries overcome the average income trap. Many of these, which have successfully transitioned to the status of high-income countries, have strong insurance markets, and this is no coincidence: insurance markets contribute significantly to resilience, to the crucial ability to cope with crises, facilitating thus the poorer countries have the opportunity to escape the middle income trap. In this context, the insurance industry needs to help close the gap by focusing on simpler products, risk prevention and building public-private partnerships, whether it is risk protection or infrastructure investment. Several studies have shown that higher insurance penetration is associated with a significantly faster recovery and lower long-term consequences. At the same time, insurance significantly facilitates access to credit. Life insurance providers are important financial intermediaries and therefore become an important source of long-term capital that allows investment at both the macro and micro levels.

Despite the progress made in recent years, significant gaps remain in insurance coverage. Covid-19 and the associated increase in risk awareness, as well as the orientation towards sustainable investment offer a unique opportunity to reduce some of these gaps. For the insurance industry, this generates four strategic recommendations.

First, products need to become simpler and easier, and the digitization process is at the heart of their accessibility. For example, in the field of health: the ‘phygital’ model is on the rise and offers the possibility, especially to less developed countries, to facilitate the access of more people to health services. With the help of Big Data and new technologies, risks can be predicted much more easily and independent business models can be developed to prevent them. Covid-19 showed that we live in a world where the risks are constantly increasing. This makes public-private partnerships necessary in many areas to build appropriate risk protection schemes. Lastly, the pivot to sustainability offers new investment opportunities with more stable returns.

Bahrain, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, Slovenia and South Korea are countries that have successfully transitioned from medium to high incomes in the period 1995-2019. Saudi Arabia and Bahrain climbed the high-income scale in the early 2000s as oil prices since then boosted tax revenues and sustained rapid economic growth. Meanwhile, South Korea, along with other Asian tigers, is one of the few examples of successful industrialization leading to wealth. But most of the successful high-income transitions of 1995 are in EU Member States, including Malta, Portugal and five Central and Eastern European countries.

To get rid of the middle income trap, resilience is becoming an increasingly important feature. Analysts predict that populations in richer countries will be largely immune in 2022 and expect social interaction to return to normal early next year. For emerging countries, this stage is still a long way off, with Covid-19 continuing to hamper economic development over the next two years. To these are added the rapid increase in public debt, which limits the scope of action, especially if interest rates begin to rise in the coming years. This would also be a disproportionate burden for poorer countries. In addition, the pandemic may have accelerated long-term structural trends, which will not be favorable to many emerging economies.

Even before Covid-19, growing trade disputes and increased protectionism caused a slowdown in international trade. After Covid-19, trade could be affected by the shift to sustainability, and the logistical capacity of globally interconnected supply chains is increasingly being called into question. At the same time, Covid-19 accelerated the digitization process. Big Data, artificial intelligence and connected automation will permanently change the way we work. The comparative advantages of relatively cheap labor – on which the rise of emerging markets and the global middle class in recent decades has been based primarily – would count less in this new world. One last long-term trend worth mentioning is the transition to a green, sustainable economy. The decarbonisation of the global economy will lead to an investment boom – especially in richer countries. At the same time, consumer demand in these countries will undergo a structural transformation. They will focus on sustainable products, local producers, the circular economy and the shared economy, impacting on the economic models of many emerging markets, whether they are suppliers of raw materials or producers of goods.

External commitment and regionalism

The success of the new EU Member States in scaling up revenues suggests that external commitments for deep and comprehensive structural and institutional reforms are an effective solution for middle-income countries. The EU accession process requires candidates to systematically improve the political, business and investment environment. During this process and after joining the EU, a new member country then benefits from strong integration into regional trade, technology transfer, innovation and low funding risks.

Could the success story of EU member states be a model for middle-income countries in other regions?

In theory, this would be a good recommendation for policy makers in emerging markets elsewhere. In fact, the founders of regional institutions such as ASEAN and APEC in Asia and Mercosur in Latin America intended to create common economic zones following the EU model. In practice, however, there seems to be little opportunity to achieve in today’s world. APEC and ASEAN provide some anchorage for emerging markets in Asia, but mainly in terms of deepening trade between those member economies. But beyond trade, significantly different political values and institutional norms, as well as transnational conflicts in the region, will prevent deeper integration and strong agreements that would accelerate reforms.

:quality(80)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/SNIPPETS-REALTY-2024_ionut-urecheatu.png)

:quality(80)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/22C0420_006.jpg)

:quality(80)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/COVER-1-4.jpg)

:quality(80)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/br-june-2.jpg)

:quality(50)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/VGP-Park-Timisoara_-8thbuilding_iulie-24.jpg)

:quality(50)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/America-House-Offices-Bucharest-Fortim-Trusted-Advisors.jpg)

:quality(50)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/BeFunky-collage-33-scaled.jpg)