:quality(80)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Optimef.jpg)

Thanks to recent initiatives by young local entrepreneurs, Romanians can ride their Reghin skis like it’s the ‘60s, check the time on an Optimef wristwatch like it’s the ‘70s, and drink Rahova beer like it’s the ‘80s. With this, the bittersweet longing for aspects of life under communism, known as Ostalgia, is making a fresh comeback fuelled by brand nostalgia.

The relaunch of popular communist brands is not a recent phenomenon. Happening everywhere across Central and Eastern Europe from Slovakia to Poland to Russia, it is part of a wider movement, which, like most cool things, originated in Berlin. Coined in the German capital in the early ‘90s by an East German cabaret artist, Ostalgia (a portmanteau of the German words Nostalgie, meaning nostalgia, and Ost, meaning east), describes a phenomenon that by the end of the ‘90s had already created in the former GDR a booming “nostalgia industry” – the revival, reproduction and sale of East German products.

Locally, several products sold under communism survived the sudden meeting with capitalism. Eugenia, the cream-filled biscuit sandwich and one of the country’s most popular snacks, is still made by the original producer, the 100 percent Romanian-owned Dobrogea Grup, while Dacia, Romania’s flagship car and one of the country’s top export products, has been made by Automobile Dacia, a subsidiary of the French car manufacturer Renault since 1999. Most traditional Romanian brands of sweets, detergents, beers and more sold under communism are now part of the portfolio of multinational companies. Most – but not all. Among the independents, the most popular bike brand, Pegas, was forgotten until 2012, when local entrepreneur Andrei Botescu registered the trademark and, with capital of EUR 70,000, one year later started production. Revived, revamped, recently franchised and poised for international expansion, to date Pegas is the most successful entrepreneurial story involving an iconic Romanian product. Three brands, recently revived by millennial entrepreneurs, fall into the exact same category. So what motivated them?

A modern take on an iconic beer

For his project, which brought to the market a beer bearing the name Rahova, a tribute to the legendary Bucharest-made brew that was once the most popular in the country, Radu Dura (38) sought not to recreate the exact iconic beer, sold until the end of the ‘90s, but to capture the spirit of the “neighbourhood beers” of that time.

He started the ‘Bucuresti de cartier’ project with Doru Rusanescu (39) in March 2018. The two had partnered three years prior to build a company around their flagship product Rasta Monsta, an energy drink now sold in most major supermarkets. Having each worked for over ten years in the beverage industry before turning to entrepreneurship, they shared the relevant background, necessary expertise and passion needed to kick off new projects. The launch of the new range of craft beers, Dura explains, was a way to diversify their product portfolio and bring back the spirit of Bucharest’s legendary beers. Their modern labels depict landmarks of neighbourhoods against pastel backgrounds. “I’m not even sure I ever got to taste the original Rahova beer myself,” Dura says, “because I was still a child at the time it was on its last legs.”

Although he was just nine when communism fell, in the aftermath of the 1989 Romanian Revolution, his memories of the beers are vivid. “Communist beers were a fixture at grownups parties,” he recalls. “They were chilled in large galvanised steel boilers, using large chunks of ice – boulders, to be precise, and not ice cubes, as we have now. Their labels, made of thin paper, would quickly get soaked, peel off and float away, rendering them anonymous,” he recalls. “They tasted very bitter, especially to us as children, due to the hops which they used in a good measure to ensure a longer shelf-life,” says Dura, who started working for several local beer distributors while still in college, about ten years into capitalism.

By then, the Romanian beer market had already experienced major changes. An excise tax cut on beer in 1997 had made the local business environment very friendly for brewers. Around that time, the first large international brewers entered the market, and their market share rose under the positive auspices. By 2004 they had strengthened their presence by buying some of the biggest local factories. The move meant the labels consumers had drunk for generations went off the market.

Then, as local consumers got exposed to a larger variety of beers, including global brands, consumers’ preferences changed, or, as Dura describes it, went through a process of “emancipation”.

Nevertheless, according to Dura, traditional beers’ appeal was enduring enough to make diehard fans look for them even after they had disappeared from the shelves. “Around 2000, when I started working for Bucharest’s beer distributors, the names of the beers I had heard about as a child from the grownups around me, such as Rahova, Bucuresti, Cismigiu and Ateneu, started to pop up in conversations with clients.”

The first beer Dura and his partner produced, a light lager, was sold under two labels: Rahova, celebrating the memory of the former beer factory, closed and in ruins since 2011, and Pantelimon.

Five months later, after Rusanescu left the project, Dura attracted a new partner, Bauturi Speciale, and put on the market a new beer, an IPA, which is sold under labels representing another two neighbourhoods: Drumul Taberei and Dristor.

Having started with an investment of EUR 20,000, Dura and his partner make their beer in a small brewery in Crangasi, started by a trio of craft beer enthusiasts that go under the name of Three Happy Brewers. Whether they will continue to be what the industry has dubbed “gypsy brewers” for long is still something they have to decide on.

The right people at the right time

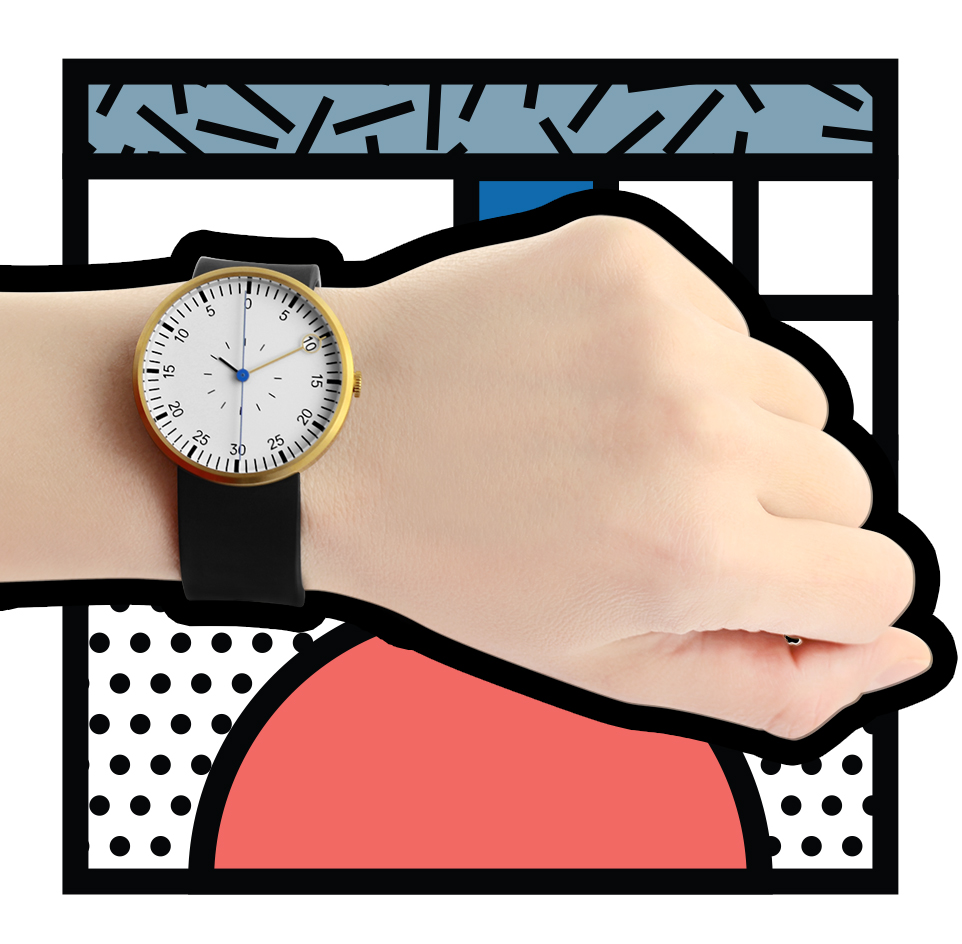

The co-founders of Optimef, the modern successor of Romania’s first watch, are Andrei Morariu (30), an actor, and Bogdan Costea (37), an architect. The two met at a film festival and the experience turned out to be very valuable for the task of reviving Romania’s first watch. “We learned then the stages of implementing a project from the idea and until the final product; it was then that we also had our first contact with such notions as branding and advertising. All of them were outside of our area of expertise and helped us a lot when we launched Optimef,” Morariu outlines.

“It all started back in 2014 with the question: What happened to the watch-making industry in Romania?” he recalls. With an EUR 30,000 investment from their own savings, family money and that of a friend they like to call ‘business angel’, they took on the task of reviving what had been described at the moment of its launch, in 1979, as a “modern, accurate and reliable” watch.

Two years passed between the time the entrepreneurs started the project and the moment they put the first Optimed on their wrists.

The first challenge was unexpected: finding a working original Optimef watch turned out to be impossible. Optimef watches are rare finds, as they were discontinued two years after launch. “It was a liquid-crystal display clock that made it less popular than the successors of Cromef and Orex,” Morariu notes. As for getting in touch with the original producers of the ‘70s watch, that also proved unviable. Mecanica Fina is currently owned by an Italian businessman who did not continue making watches after taking over the plant. They responded in typical millennial fashion, doing their research exclusively online. “We found images of all the models launched, the technical specifications, the box they were packed in, the Scanteia newspaper clippings and factory pictures,” Morariu says.

Later, the project suddenly seemed hopeless when the two started looking for a manufacturing site. “While the creation side, the design and defining the concept went smoothly, we were immediately discouraged by the production possibilities available in Romania,” the entrepreneur recalls. “So we began to study several international boutique brands – the niche where we wanted to position ourselves – and try to track the steps taken for their products, up until the production stage.” All roads led to Hong Kong. Several weeks of phone calls and market prospecting later, we decided to go there for a few appointments. That’s how we got to meet the producer we’re working with now. From that moment on, things went smoothly again, exactly under the terms and conditions we agreed at the beginning. The mechanism comes from Japan, the case from Shenzen, and the final assembly is done in Honk Kong,” he says.

Then, as neither had any retail experience and had not done market research prior to starting their project, they faced a fresh challenge in positioning the new brand. “From the beginning, we relied on the uniqueness of the idea, the quality of execution and on… nostalgia,” Morariu says.

For the two first-time entrepreneurs, reviving iconic brands and making them successful today represents a means of making peace with the past. “We decided to relaunch Optimef to remember that cool things were happening in Romania before we even knew what ‘cool’ meant. Hence our slogan: Some Romanian cool. Again,” says Morariu.

He adds, “Of course, there is a lot of responsibility involved when you decide to ‘touch’ something old compared to launching a new brand, but we enthusiastically accepted this challenge. We’ve treated the Optimef project since the beginning as one leading to a rebirth, not as a continuation of the old brand.” “A nice surprise we had after the launch,” Morariu recalls, “was to be contacted immediately by several people who had worked at Mecanica Fina in the ‘80s.” And the prospects are positive. In their first business year, they posted a EUR 50,000 turnover.

Taking the big jump

Apart from being skiing enthusiasts, Sebastian Big (38) and Patiu Ionut (39) have a background in product design and sales. For reviving and bringing to the market their version of the Reghin Skis, they needed all those skills and more. “We did just about everything, from the design to website integration with a payment platform, from marketing and PR to primary accounting and conducting tests in the resorts,” Big says. That, he explains, drove down the amount invested, to EUR 50,000.

“The idea to revive the brand popped up in a conversation we had about four years ago. That was followed by two years of research to see what ski production and what a company producing skis really meant,” Big recalls. “We are both skiers and were pretty knowledgeable, but we had to learn how to switch positions, from consumers to producers.”

“Ideas we had aplenty,” the entrepreneur says, “but it was important to discard a lot of them fast, because they were not viable. One of them was producing the skis in Romania. “We quickly concluded that it would be extremely expensive, both from the point of view of the infrastructure, as well as the final cost of the product.” That is why they decided to produce the skis in the Czech Republic, in a factory with a tradition of over 100 years, he explains.

Then, an important part of the process was to find and establish a relationship with producers, Big says. Also, learning the trade was not easy, as “there is no direct competition, so we could not learn from others,” he adds. “We then we built a website with a payment platform. We believe that online sales are already the future of sports equipment.”

For the Baia Mare-born entrepreneur, his first memory of the original Reghin skis was an important emotional factor in deciding to enter the venture. Still, he would not bet the brand’s entire marketing strategy on nostalgia alone. “My first memory was of going with my dad to the ‘famous’ store Foto Muzica si Sport and buying two pairs of Reghin Combi-R skis, a yellow pair for me and a blue pair for him,” the entrepreneur recalls. “Of course I liked the blue ones more, because they were for adults, and afterwards that was all I could think about… that I couldn’t wait to grow up, to wear the blue ones!”

But although, Big argues, “the original product is obviously associated with our childhoods, with a space marked by freedom, which fits well with the idea of skiing,” though popular and accessible, the original Reghin skis were far from top notch. “Their level of quality was not ideal, and this is what the new Reghin skis want to fix. So basically our vision revolves around the idea of quality skis at affordable prices.

:quality(80)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/1_Transport.jpg)

:quality(80)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/IMG_6951.jpg)

:quality(80)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/COVER-1.jpg)

:quality(80)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/cover-april.jpg)

:quality(50)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/0x0-Supercharger_18-scaled.jpg)

:quality(50)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Schneider-Electric-anunta-castigatorii-Sustainability-Impact-Awards-2023-in-Romania-scaled.jpg)

:quality(50)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Premier-Energy-Group-1.jpg)